PCR is one of the most trusted techniques in molecular biology because it can turn a tiny amount of DNA into a clear, measurable signal. When it’s set up well, it’s fast, sensitive, and wonderfully repeatable. If a run doesn’t look right—no bands, faint product, extra bands, or results that vary—think of it as helpful feedback from the workflow, not a dead end. With a calm, stepwise check, you can usually bring the reaction back to strong, clean performance quickly.

The encouraging news is that most PCR problems come from a small set of fixable variables: template quality, primer design, polymerase chemistry, cycling conditions, and contamination control. Once you identify which part of the workflow is drifting, you can restore strong, clean PCR amplification quickly and confidently. This PCR Troubleshooting guide explains the most common result patterns, why they happen, and the most reliable PCR Solutions to try—using minor, focused adjustments that save time and keep your workflow simple.

Why PCR Troubleshooting Matters

A PCR result is rarely “just a band.” It often drives downstream decisions—cloning, genotyping, Sanger sequencing, qPCR validation, or a key figure in a manuscript.If amplification is inconsistent, it’s simply a sign that a couple of controllable settings need a quick adjustment—so you can get back to smooth, reliable results while using your reagents efficiently and staying confident in your samples.

A structured troubleshooting workflow helps you:

- Identify the root cause faster (rather than chasing symptoms).

- Improve reproducibility across users and days.

- Protect downstream workflows from bad inputs.

- Reduce repeats, reruns, and preventable reagent waste.

Most importantly, it helps you build a PCR setup that stays stable as your project scales.

A Simple Framework That Fixes Most PCR Problems

Before diving into specific issues, use this three-step framework. It turns “mystery PCR” into a predictable diagnostic process.

Step 1: Confirm the basics

Make sure your target is real and detectable:

- The template contains the target region.

- The primer binding sites are correct.

- The expected amplicon size is reasonable for your polymerase and cycling time.

- You have appropriate positive and negative controls.

Step 2: Isolate the failing stage

Most PCR problems and solutions map to one of these stages:

-

Template quality and inhibitors

-

Primer behavior (specificity, dimers, mispriming)

-

PCR reaction chemistry (Mg2+, dNTPs, polymerase, additives)

-

Cycling conditions (annealing temperature, extension time, cycle count)

-

Post-PCR analysis (gel conditions, staining, loading)

Step 3: Change one variable at a time

If you change polymerase, Mg2+, primers, and annealing temperature all at once, you can’t learn what actually fixed the issue. Make single, intentional changes and record outcomes.

Quick Diagnostic Checklist (Start Here)

When a PCR reaction doesn’t perform as expected, these checks catch a surprising number of issues fast:

- Confirm your master mix and enzyme were stored correctly and kept cold during setup.

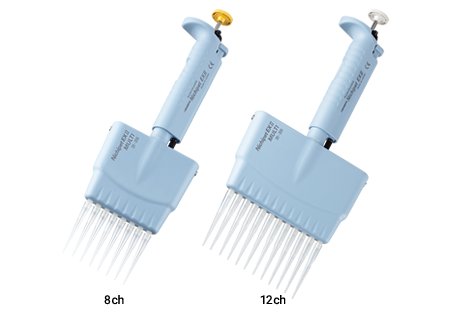

- Verify pipettes and tips (especially after a busy week or shared bench use).

- Use fresh nuclease-free water and clean aliquots of MgCl2, dNTPs, and primers.

- Check that the thermocycler program matches your polymerase requirements.

- Confirm that your gel and ladder are correct, and that you loaded enough product.

- Run a known-good positive control template with the same mix.

Common PCR Problems and the Most Reliable PCR Solutions

Problem 1: No Amplification

What you see

- No product band in the sample lanes.

- Sometimes the positive control also fails.

Most common causes

-

Most of the time, this pattern has a straightforward cause you can fix quickly such as low or inhibited template, primers that need a small design or concentration adjustment, an annealing temperature that’s slightly too stringent, an extension time that’s a bit short for your amplicon, polymerase performance affected by storage/handling, or a simple missing reaction component in manual setups. The best next step is to start with clear controls, because they immediately show whether the solution is in the reagents/program or in the sample.

PCR solutions that usually work

Start with controls. If your positive control doesn’t perform as expected, it’s a helpful signal to focus on reagents or cycling settings first, before changing your sample strategy.

Confirm reaction composition

A quick way to catch missing components is to rebuild a fresh master mix from aliquots and check off each component as you add it. Many labs also add a tracking dye to the master mix (when compatible) to reduce missed additions.

Lower annealing temperature in a controlled way

If you suspect annealing is too strict, reduce annealing temperature by 2–5°C and rerun. Better yet, use a gradient PCR if available.

Increase template input slightly.

For low-copy templates, a modest increase in input can help. Avoid overloading, though—too much template can introduce inhibitors or raise nonspecific amplification.

Extend extension time

If you’re amplifying a longer product, increase extension time (based on polymerase speed). Try a different polymerase chemistry If the target is GC-rich, long, or complex, standard Taq may struggle. A high-fidelity or hot-start enzyme often improves PCR amplification and specificity.

Problem 2: Weak or Faint Bands (Low Yield)

What you see

- A product appears at the expected size, but it’s faint.

- Replicates vary or require many cycles to show.

Most common causes

- Low template concentration or partial degradation

- Suboptimal Mg2+ or primer concentration

- Insufficient cycle number

- Annealing temperature slightly too high

- Inhibitors in the template prep

PCR solutions

Optimize Mg2+ and primer concentration.

Magnesium affects enzyme activity and primer-template binding. If the yield is low, test a small Mg2+ range rather than guessing. Add a few cycles, but don’t rely on cycles alone. Increasing cycles may help, but if chemistry is off, more cycles can amplify the background, too. Use cycles as a fine-tuning step, not the primary fix.

Improve template quality

If you’re working from crude lysates, plant tissue, blood, or environmental samples, inhibitors are common. A quick cleanup step often increases yield more than any cycling tweak.

Use additives for difficult templates

For GC-rich regions, DMSO, betaine, or other enhancers can improve denaturation and primer access. Use them carefully and test a small range to avoid over-suppressing polymerase activity.

Problem 3: Nonspecific Bands (Extra Bands)

What you see

- Multiple bands

- A band at the expected size, plus additional products

- Sometimes a “ladder-like” pattern

Most common causes

- Annealing temperature is too low

- Primer design with off-target binding sites

- The primer concentration is too high

- Mg2+ too high (reduces stringency)

- Too many cycles

PCR solutions

Increase annealing temperature gradually.

Raising annealing temperature improves specificity by reducing weak primer binding. A 2–4°C increase can dramatically clean up products.

Use hot-start polymerase

Hot-start enzymes prevent early, low-stringency priming during reaction setup and initial heating. This is one of the most consistent PCR solutions for nonspecific amplification.

Reduce primer concentration

If primers are too concentrated, they can bind imperfect sites more often. A modest reduction often improves specificity without killing yield.

Redesign primers if needed.

If off-target binding is likely, primer redesign is the long-term fix. Aim for balanced GC content, avoid self-complementarity, and verify uniqueness against your target genome if possible.

Problem 4: Primer Dimers (Small Band Near the Bottom)

What you see

- A low-molecular-weight band (often 50–100 bp)

- Smears or extra signal at the bottom of the gel

- In qPCR, melt curves show a low-Tm peak

Most common causes

- Primers are complementary to each other (especially at the 3’ ends)

- The primer concentration is too high

- Annealing temperature is too low

- Inadequate hot-start control

- PCR solutions

Use hot-start polymerase and keep the setup cold.

This reduces primer-dimer formation before cycling begins.

Raise annealing temperature

Even a slight increase can reduce weak primer interactions.

Lower primer concentration

A modest reduction often improves the signal-to-noise ratio.

Redesign primers if dimers persist.

If the 3’ ends are complementary, primer redesign is often the cleanest fix.

Problem 5: Contamination (Bands in the No-Template Control)

What you see

- Amplification in the NTC (no-template control)

- Unexpected bands across many reactions

Most common causes

- Amplicon carryover from previous PCR products

- Cross-contamination during pipetting

- Aerosol contamination from opened tubes

- Shared reagents that have been exposed repeatedly

PCR solutions (high impact)

Separate pre-PCR and post-PCR areas

This is one of the best long-term controls. Even a simple separation—different bench zones and dedicated pipettes—helps.

Aliquot reagents

Small aliquots reduce repeated exposure and make it easier to discard a single contaminated tube rather than an entire stock.

Use filter tips and a careful workflow.

Filter tips reduce aerosol transfer. Also, avoid touching tube rims with pipette tips.

Consider dUTP/UNG carryover prevention (when compatible)

For workflows prone to carryover, enzymatic prevention strategies can dramatically reduce contamination.

Problem 6: Inconsistent Results Between Replicates

What you see

- The same sample gives different yields or band patterns

- Replicates vary across wells or tubes

Most common causes

- Pipetting variation (small volumes amplify errors)

- Evaporation or poor sealing (especially in plates)

- Uneven thermocycler performance across the block

- Reagents not mixed thoroughly

- Degraded or repeatedly thawed components

PCR solutions

Build a master mix

A master mix reduces pipetting error and keeps reagent ratios consistent.

Mix gently but thoroughly.

Incomplete mixing can create concentration gradients, especially with Mg2+ and primers.

Improve sealing and reduce evaporation.

Use high-quality caps or seals, confirm plate compatibility, and ensure consistent spin-down before cycling.

Check thermocycler calibration and uniformity.

If variability tracks with specific block positions, instrument uniformity may be the issue.

Problem 7: GC-Rich or Difficult Templates (Amplification Fails or Looks Messy)

What you see

- No band or weak band, even with correct primers

- Smears or multiple products

- Sensitivity to small temperature changes

Most common causes

- Strong secondary structure in the template

- Poor denaturation at standard temperatures

- Primers struggle to bind consistently

PCR solutions

Use a polymerase designed for GC-rich templates.

Some enzymes and buffer systems are engineered for challenging targets.

Add a GC enhancer (tested carefully)

DMSO or betaine can improve denaturation and primer access. Start low and titrate.

Increase denaturation time

A slightly longer denaturation step can help stubborn GC regions.

Use touchdown PCR

Touchdown approaches start at a higher annealing temperature and gradually reduce it, improving specificity early on.

PCR Reaction Optimization: A Practical “Minimal Change” Approach

When you want to optimize a PCR reaction while keeping things organized, use a controlled set of experiments that isolates the variables most likely to help.

1) Start with a slight gradient for annealing temperature

Annealing temperature is one of the fastest levers for both yield and specificity. A gradient run lets you see where your primers behave best.

2) Titrate Mg2+ (especially if you’re mixing components manually)

Mg2+ influences enzyme activity and stringency. Too much can increase nonspecific bands.

3) Adjust primer concentration

If you see dimers or nonspecific products, primer concentration is a safe variable to tune.

4) Evaluate polymerase choice

Hot-start often improves clean amplification. High-fidelity enzymes improve accuracy. GC-capable mixes help difficult templates. Choose based on the goal and target.

Best Practices to Prevent PCR Problems Before They Start

Even the best PCR troubleshooting guide is most useful when you don’t need it often. These habits reduce troubleshooting frequency and improve consistency.

Keep pre-PCR workflow clean and consistent.

Use dedicated pre-PCR pipettes. Keep primers and master mixes in clean aliquots. Open tubes carefully and avoid working near post-PCR products.

Control freeze-thaw cycles

Repeated thawing slowly reduces performance for some enzymes and reagents. Aliquot when possible and keep stocks organized.

Use positive controls and NTCs routinely.

Controls make your next step clear. A positive control tells you the reagents and program can work. A no-template control tells you whether contamination is present.

Document the “winning” conditions.

Record primer lot, polymerase lot, buffer composition, annealing temperature, and any additives used. A small notebook entry can save days later.

FAQS

What is the most common reason PCR fails?

The most common reasons are simple, fixable setup details—such as a missing component, template quality that can be improved with a quick cleanup, or an annealing temperature that’s a bit too stringent for the primer set. A positive control plus a simple gradient often reveals the root cause quickly.

How do I increase PCR yield?

Improve template quality, optimize Mg2+ and annealing temperature, confirm extension time is sufficient, and consider a hot-start or specialty enzyme if the target is difficult.

How do I reduce nonspecific PCR amplification?

Increase annealing temperature, reduce primer and Mg2+ concentration if needed, reduce cycle number, and use a hot-start polymerase to prevent early mispriming.

How can I prevent PCR contamination?

Separate pre- and post-PCR areas, use aliquoted reagents, use filter tips, and keep NTCs in every run so contamination is detected early.

How many cycles should I run in a PCR reaction?

Most standard reactions perform well in a moderate cycle range. If you find you need more cycles to see a product, take it as a helpful hint that a small improvement in reaction chemistry or template quality could unlock stronger yield—so you can get clear results without relying only on higher cycle count. Adding cycles can amplify the background along with your target.

Why do I get a band in my no-template control?

This typically indicates contamination from previous amplicons, aerosols, or shared reagents. Replace suspect reagents with fresh aliquots, clean the workspace, and tighten pre-PCR workflow separation.

What’s the difference between PCR troubleshooting for genomic DNA vs plasmid DNA?

Plasmid DNA is usually cleaner and easier to amplify. Genomic DNA is more complex and can carry inhibitors from the extraction. For gDNA, primer specificity and template quality become even more critical.

Can changing polymerase really fix most PCR problems?

Yes—especially when nonspecific priming, GC-rich targets, or difficult templates drive issues. Hot-start and specialty enzyme systems often provide cleaner amplification with less optimization.

Conclusion

PCR is reliable because it follows predictable rules—when the template is clean, primers are specific, the reaction chemistry is balanced, and cycling conditions match the target. When results look wrong, you don’t need to start over from scratch. A calm, stepwise PCR Troubleshooting approach usually reveals the issue quickly. If you remember one thing, make it this:

Treat troubleshooting like a controlled experiment—and stay encouraged, because most PCR issues have straightforward fixes once you isolate the variable. Use good controls, isolate the failing stage, and test one change at a time. That’s the fastest way to move from recurring PCR Problems to stable, repeatable PCR amplification. If you’re standardizing your workflow, consider building a consistent supply set—from enzymes and buffers to nuclease-free consumables—so your team can spend more time on data and less time on reruns.